UVA hosts the state’s first Normal School, a summer program for Virginia primary school teachers. The program draws almost 500 students, 312 of whom are women. The courses offered are intended to satisfy requirements for teacher certification but do not lead to degrees. Only men can earn credit and degrees for the courses they took.

That same year, the faculty and Board of Visitors vote against admitting women under any conditions.

The Society for Extension of Female Education submits a petition by 400 Virginia teachers to the Board of Visitors at the University of Virginia, requesting that women be allowed to matriculate. Caroline Preston Davis, daughter of a faculty member, applies to UVA to take the bachelors-level math exams. The Board of Visitors (BOV) approves her application provided she pay a fee and test separately from male students. She passes with distinction and receives a Certificate of Proficiency instead of a diploma. Davis becomes the first woman to receive official recognition for her studies at the University.

Fannie Littleton Kline is the first woman to attend UVA as a “special student” studying chemistry privately with Professor William Mallet.

“The faculty have now come to the conclusion that, upon the whole, admission of women to the University would be unwise and injurious to the best interests of the University.”

– William M. Fontaine, head of the committee charged with investigating the admission of women

The BOV votes against coeducation at UVA with the explanation that giving women higher education will “physically unsex” them, causing them to lose their power in the home.

By this time, 71% of US colleges and universities are coeducational. UVA remains a “gentleman’s university” and Virginia will be the last state in the union to provide post-secondary coeducation.

The nurse training program begins at UVA with seven female students, making nursing students the first women to attend UVA regularly. However, the University refuses to support accreditation and does not allow the program to grant degrees until 1949.

The School of Education establishes a summer school for teachers. Women are admitted, but the courses offered are intended to satisfy requirements for teacher certification and do not lead to degrees. Women can also take classes in home economics, cooking and stock judging (the examination of domesticated animals for breeding purposes).

The Equal Suffrage League forms and Mary Munford presses the Virginia General Assembly to establish a coordinate women’s college in Charlottesville.

UVA faculty endorse Mary Munford’s bill to establish a women’s college in Charlottesville; it fails at the legislative level.

Georgia O’Keeffe attends the University for four summers, taking classes and later teaching them between 1912 and 1916.

Patient overcrowding in the hospital and a measles outbreak results in the adaptation of Varsity Hall in 1914 from its initial use as an infirmary to accommodations for nursing students. Nursing students went on to live in Randall Hall, starting in 1919, and McKim Hall, which was built in 1931.

The bill to establish a women’s college at UVA fails in the General Assembly by two votes despite having UVA President Edwin A. Alderman’s support. William & Mary becomes fully coeducational in 1918 as an alternative.

President Alderman asks faculty to admit women to graduate and professional schools, under the condition that they’re at least 20 years of age and have two years of experience at another school.

“By action of its Rector and Visitors, taken January 12, 1920 and effective with the opening of the session of 1920-21, the University of Virginia offers to women of maturity and adequate preparation opportunity in the College for specialized training and for graduation with a vocational baccalaureate degree….”

Congress passes the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, giving women the right to vote. By this year, two-thirds of American colleges are coeducational.

In January, the measure allowing some women to enroll in graduate and professional schools at UVA passes the faculty 64-4 and the Board of Visitors 7-2. The Virginia General Assembly passes the bill.

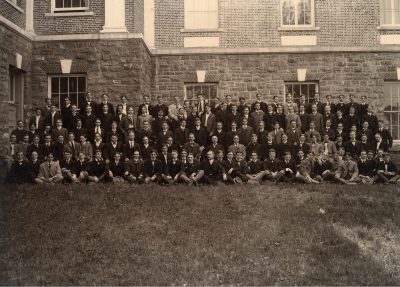

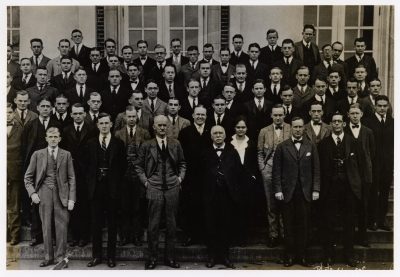

The Board of Visitors composes age and education requirements for women applicants. Seventeen women enroll at UVA in the fall of 1920: three in Law, four in Medicine, three in Education, and seven in Arts & Sciences.

The Board of Visitors appoints 29-year-old Adelaide Simpson as head of the University’s female students, thus establishing the Office of the Dean of Women. Simpson was asked to focus on the development of leadership, social poise and integrity of female students, and to be available to them for guidance and consolation.

Emilie Watts McVea becomes the first woman appointed to the Board of Visitors.

Sarah Ruth Dean of Mississippi is the first woman to graduate from the School of Medicine.

Elizabeth N. Tompkins of Albemarle County, Virginia, is the first woman to graduate from the UVA Law School in 1923. After graduating, Tompkins clerks for two years in Charlottesville before relocating to Richmond for a distinguished 54-year legal career. She is also the first woman admitted to the Virginia State Bar.

A group of women forms a small local sorority named Pi Chi. In 1932, Pi Chi becomes affiliated with the national sorority Kappa Delta.

Lila Bonner becomes the first four-year graduate of the School of Medicine.

At 118 enrolled, women constitute 5% of the University’s total enrollment.

Chi Omega is the first national women’s fraternity established at UVA (before the term sorority was in use, and almost a half-century before undergraduate admissions would fully enroll women).

Thelma Brumfield Dunn (Med class of ’66) becomes the first female faculty member at the School of Medicine.

The Co-Ed Room on the West Range provides a women-only space to gather for meals or other social events. The room features cards and card tables, a piano, a radio, and several current magazines, providing women with a place to unwind without being reminded of their minority status. Betty Slaughter, the Black housekeeper who staffed the Co-Ed Room, was largely responsible for the friendly, welcoming environment of the space. Students affectionately nicknamed her “Betty Co-Ed” and many considered her a friend, confidante and surrogate mother during their years here.

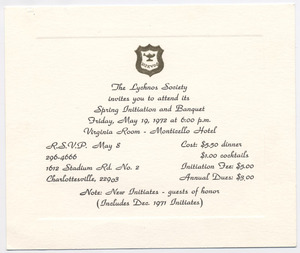

In the spring, female students establish the Lychnos Society, an honor society. Intended to be comparable to the Raven Society, which had no female members, this group recognized high standards of scholastic achievement, leadership and intellectual activities among women at the University. “Lychnos” is the Greek word for “lamp.”

Roberta Hollingsworth Gwathmey starts work as the Dean of Women, and will hold the role until 1967. During her tenure, Gwathmey expands the Dean’s role, making it an important office within University administration. She campaigns successfully successfully for the construction of the first women’s residence hall and she serves a growing population a growing population of female students during three decades of significant change.

Alice Jackson, a Black graduate of Virginia Union University, applies to a master’s program in French. Her application for graduate study is denied by the BOV, citing the state’s “fixed policy” of segregated education. Ms. Jackson’s application to UVA challenges Virginia’s compliance with the 1896 Supreme Court ruling Plessy v. Ferguson, which upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation under the “separate but equal” doctrine. At the time, the Commonwealth of Virginia did not have a graduate school for Black students, and, in response to this violation of federal law, the Virginia legislature quickly established a school at Virginia State University.

Mary Washington College in Fredericksburg becomes the “coordinate college” for undergraduate women. After two years at Mary Washington, women can transfer into the University of Virginia.

The Board of Visitors approves a proposal to establish a baccalaureate program in nursing. Although nursing faculty are responsible for the specific academic content in each program, the diploma program is under the control of the hospital, the nursing baccalaureate program is under the School of Medicine, and the baccalaureate nursing education program is directed by the School of Education.

Driven by a critical nursing shortage after World War II, nursing department director Roy Carpenter Beazley establishes a yearlong LPN (licensed practical nurse) program with Charlottesville’s Black vocational high school, Jackson P. Burley High. This program offers local students a path into nursing in the ’50s and ’60s and before desegregation. These nurses were not allowed entry into UVA because of their race but they went on to help desegregate UVA Hospital. Their presence and experiences are the first steps toward integrating the nursing profession. The LPN program continues at UVA Hospital at least until 1980, and possibly later.

The first dorm for women opens on Grounds and is named for Mary Cooke Branch Munford, a member of the Board of Visitors who labored tirelessly for either equal admission of women to the University or the establishment of a coordinate college near the University. Mary Munford Hall (currently the IRC) could accommodate up to 104 women, and all female students except for nurses and married women were required to live there. The dorm provided much-needed space for women to socialize and pursue recreational activities.

E. Louise Stokes Hunter is awarded a doctorate in education, becoming the first Black woman awarded a degree by UVA.

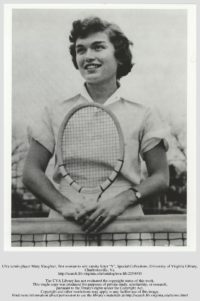

Mary Slaughter becomes the first woman to letter in any sport at the University of Virginia and the first to participate officially for a Virginia athletic team. The United States Lawn Tennis Association crowns her the Virginia State Women’s Champion in 1959, 1961 and 1963.

The Board of Visitors accepts the nursing faculty’s claim that the education of nurses is a responsibility of the University and establishes the School of Nursing as one of the independent schools within the academic community.

Doris Khulmann-Wilsdorf becomes the first female full professor at UVA outside of the School of Nursing, teaching engineering and physics.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 is passed and signed into law.

There is concern that UVA is falling behind coeducational institutions, especially since its all-male counterparts (Yale, Dartmouth, Princeton) were all moving towards coeducation. The BOV charges President Shannon with studying coeducational issues, specifically: Does the present system discriminate against women? Would academics improve with women? Would social life improve with women?

Barbara Starks Favazza (Med class of ’66) becomes the first Black woman to graduate from the UVA School of Medicine.

UVA hires Elizabeth Johnson as the Assistant Dean of Admissions in 1969. As the University’s first full-time Black admissions officer, Johnson makes it her priority to recruit and retain Black students at a time when they make up less than one percent of the University’s total undergraduate population.

President Edgar F. Shannon Jr. questions whether UVA could attain a reputation as a first-class institution while excluding women students. The Board of Visitors requests President Shannon conduct a study on the issue of coeducation.

The committee studying coeducation at UVA recommends that the University remove all restrictions on admitting women and Black students. The Student Honor Committee issues its own report stating the admittance of women “would hurt the honor system.” President Shannon appoints a committee under Provost Frank Hereford (Col class of ’43, Grad class of ’47) to address the practical considerations of admitting women, such as the impact on dormitories.

The Board of Visitors appoints Provost Frank Hereford and a coeducation committee to develop a plan to gradually admit women to UVA over the span of 10 years and cap female enrollment at 35% in 1980.

John Lowe (Law class of ’67) files a lawsuit against the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia, stating that the University “severely discriminates against women in their admissions policies.” Lowe appeals for a change in those policies to allow women to enter the College of Arts & Sciences.

Virginia “Ginger” Scott (Col ’73, Grad ’80) of Charlottesville becomes the first woman enrolled as a first-year student in the College of Arts & Sciences. She graduates in 1973 with a degree in religious studies and later earns master’s degrees in religious studies and education from the University.

During the trial regarding the University’s admission policies, the Board of Visitors goes into a special meeting and emerges with a voluntary acceptance of full coeducation within three years. UVA accepts Lowe’s proposed transition plan for coeducation that would admit 450 women undergraduates in 1970, 550 in 1971, and admit students without regard to sex by 1972. There is no court order.

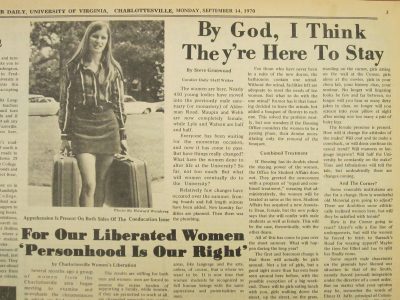

Approximately 1,000 women apply to UVA, and 450 undergraduate women enroll in the College of Arts & Sciences, transforming the University into a fully coeducational institution.

Mavis Claytor (Nurs class of ’70) becomes the first Black graduate to earn a bachelor’s degree in nursing from UVA.

Elaine Jones (Law class of ’70) becomes the first Black woman to graduate from the UVA School of Law.

In accordance with the transition plan, 2,500 women apply for admission to UVA and 550 women are admitted.

Sandra Lewis (Col class of ’72) becomes the first Black woman to graduate from the College of Arts and Sciences.

Open enrollment for women undergraduates begins at UVA. These women gain entry into UVA’s organizations, societies and leadership positions, including the IMPs, the Raven Society, the Cavalier Daily and the Honor Committee.

In 1972, Cynthia Goodrich Kuhn (Col class of ’73) moves into 28 East Lawn and becomes the first female Lawn resident.

The federal government passes Title IX, prohibiting sexual discrimination in higher education institutions that receive federal funds.

The first National Pan-Hellenic organizations are established on Grounds, with fraternity Omega Psi Phi and sororities Delta Sigma Theta and Alpha Kappa Alpha (1974).

Women’s tennis, field hockey and basketball teams achieve varsity status.

Women make up 43% of the undergraduate student body.

Federal Title IX regulations for intercollegiate athletics go into effect; by 1976, the women’s athletics program expands to include swimming, diving and lacrosse. Today, there are 13 women’s varsity sports.

UVA establishes the Women’s Studies Program and appoints Sharon Davie (Grad class of ’69, class of ’72) as its director. The program runs faculty development seminars in women’s studies and launches Iris: A Journal About Women. In 1989, Davie founds the Women’s Center, separate from the academic discipline in women’s studies.

The Women, Gender and Sexuality major starts.

For the first time, the number of first-year women exceeds the number of men.

The cross-country team wins UVA’s first women’s NCAA championship.

The Women’s Center opens to support women’s lives and leadership at the University after thousands of students, faculty and staff petition the University to establish such a center.

The School of Medicine Committee on Women is appointed by Dean Robert Carey and chaired by Sharon Hostler (Res class of ’67).

Overall female enrollment at UVA exceeds male enrollment for the first time, and has continued to do so ever since.

Alpha Kappa Delta Phi, the first Asian American interest sorority, is founded. The Multicultural Greek Council is founded in spring of 1999.

Rolling Stone magazine publishes a sensational and since-retracted story, “A Rape on Campus.” Although the story itself was discredited, it ignites University-wide introspection and leads to numerous initiatives to create a University environment free from sexual and gender-based harassment and other forms of interpersonal violence.

Carla Williams becomes the first Black woman athletics director at a Power Five conference institution.

Jenifer Andrasko (Darden class of ’10) becomes the UVA Alumni Association’s first female President and CEO.

Jennifer Wagner Davis becomes the University’s first female Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer.

Elizabeth Magill (Law class of ’95) becomes the University’s first female Executive Vice President and Provost.

Telling the story of women at UVA is a collaborative, evolving project. We look forward to expanding the narrative through Retold and welcome suggestions for additional dates or milestones to consider. If you have a recommendation for the UVA women’s history timeline, please email retolduva@virginia.edu.

Photo sources: Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, Arthur J. Morris Law Library, Corks & Curls, UVA Athletics, UVA School of Nursing and UVA Alumni Association

Sources

- Virginia Magazine

- Make way, gentlemen: How women found their way at Mr. Jefferson’s University [Fall 2020]

- Not Without a Fight: How UVA granted women full admission sooner rather than basically never [Fall 2020]

- On Common Grounds: An incomplete list of notable alumni who shared the University [Winter 2018]

- Serpentine Timeline: Some of the twists and turns of UVA history [Winter 2018]

- Women at the University of Virginia: How women fundamentally changed what once was known as a “Gentleman’s University”[Spring 2011]

- Workplace in Progress: Women professionals had their own struggles for equality at UVA [Fall 2020]

- UVA Today

- Carla Williams Named Virginia Director of Athletics [October 2017]

- Six Memorable Milestones for Women at UVA [November 2017]

- The Case for Full Coeducation at UVA Turned On a Late-Night Phone Call [September 2017]

- UVA Library

- UVA School of Law

- UVA School of Nursing

- Hidden No More [April 2019]

- Mr. Jefferson’s Nurses

- Phyllis Leffler, “Mr. Jefferson’s University: Women in the Village!”